In this blogpost, I’ll be studying the exhaustive history of film openings as to better my understanding of filmmaking as a craft. I intend to divide this post into two: film openings before Saul Bass and film openings by and after the time of Saul Bass. It must also be noted that for a significant time period in film history, cold opens weren’t used regularly so I won’t be discussing them in this blogpost. Also, for the sake of convenience, the terms ‘title sequence’ and ‘film opening’ will be used interchangeably as all the films being discussed here begin with a title sequence.

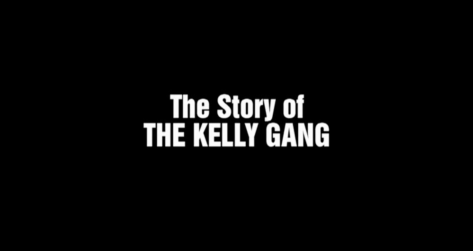

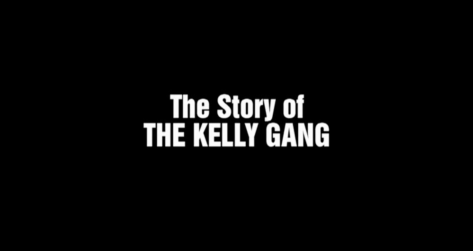

Initially, only short films were made with the first film redefining the term ‘short’ entirely. Clocking in at two point one seconds, Roundhay Garden Scene had nothing but a few people hopping about a garden. Nonetheless, the film holds immense significance in the hearts of all film friendly people as it was proof of humans being capable enough of making moving pictures. But the problem with the films of such olden times were that they had little concept of film openings. A brief, unappealing title sequence usually started the film with some shots from the film itself spliced in between. A perfect example is the first ever dramatic feature film produced, The Story of The Kelly Gang, which begins with the title of the film in full display; the words in white against a pitch black backdrop.

As we can see, the entire frame looks dull and unambitious plus tells us nothing about the film. Using a range of techniques to make the film opening more ‘linked’ with the rest of the film was something popularised by the great Saul Bass.

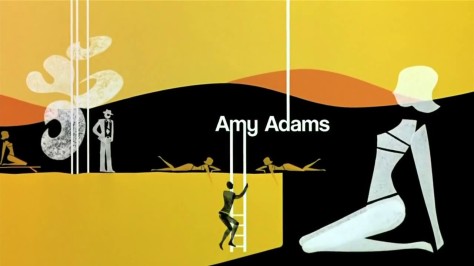

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

These two frames appear one after the other in the exact same order and show how, in order to not make the title sequence too humdrum, the director often added a few frames which showed the actor whose name was being displayed during the title sequence. Yet still, it did little to arouse the interest of the audience.

Then as film progressed and usage of colour and sound was introduced (in ’27 and ’35, respectively), directors became more ambitious and innovative with their crafting of the opening scene.

A fine example of directors executing their vision in the opening scene as well and taking into full consideration the importance of it is Gone With the Wind. Its opening scene, stellar as it is, fully encapsulates the grandeur of the film that follows. The blinding score, loud use of colours and the brilliant attention to detail in the mise en scène all suggest to a very grand film awaiting us, the audience.

In the still above, we can clearly see a lavish plantation house with lush lawns and the following shot of African-American slaves working in the cotton field denote to the fact that the plantation in itself is huge.

Yet still, it wasn’t until Saul Bass and his eclectic taste in designing title sequences that Hollywood fully realised the true potential of the opening sequence. From Otto Preminger’s The Man with the Golden Arm in 1955 to Martin Scorsese’s Casino in 1995, all of Bass’ works reflect his thorough and unparalleled understanding of the dynamics of the title sequence.

As Bass himself stated:

“My initial thoughts about what a title can do, was to set mood and the prime underlying core of the film’s story, to express the story in some metaphorical way. I saw the title as a way of conditioning the audience, so that when the film actually began, viewers would already have an emotional resonance with it.”

In his first title design, Bass masterfully constructs a near one and half minute sequence replete with pointers to help the audience get a better know-how of the film itself.

And so, in this title sequence, Bass firstly has the overwhelming jazz score playing in the background which hints to the importance of jazz in the film. Also, by starting the film by this particular genre of music, Bass seems to connote to how integral jazz is not just to the film but also to Frankie Machine, the protagonist. We also see Bass having a white rectangle transfigure into a hand which, as it happens, seems to compliment the title itself.

And so, in this title sequence, Bass firstly has the overwhelming jazz score playing in the background which hints to the importance of jazz in the film. Also, by starting the film by this particular genre of music, Bass seems to connote to how integral jazz is not just to the film but also to Frankie Machine, the protagonist. We also see Bass having a white rectangle transfigure into a hand which, as it happens, seems to compliment the title itself.

Another famous opening credit design by Saul Bass is that of Alfred Hitchcock’s 1960 film, Psycho. The film begins with a chilling violin score and grey rectangular slabs (similar to those of The Man with the Golden Arm). The score, coupled with the disjointed way the title of the film appears help Hitchcock and Bass instil in the audience a sense of eeriness.

Hitchcock then begins the film itself with a wide angle shot of the city the film is set in and slowly zooms into the building Sam and Marion are in.

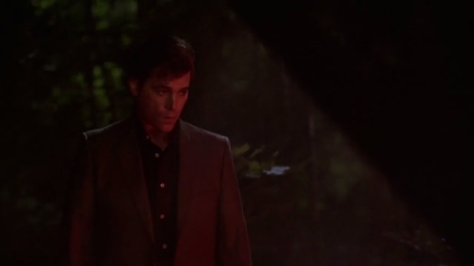

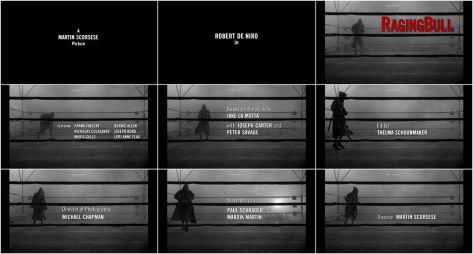

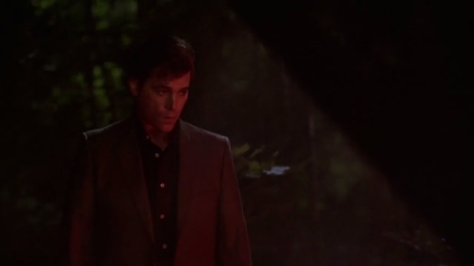

And lastly, to conclude the Saul Bass era, I’m going to look at one of the last films he worked on: Scorsese’s Goodfellas. Unlike many of his other films, in Goodfellas, Saul Bass takes a more refined and sleek look with spacing out the simplistic title credits to a good two minutes and forty three seconds. In between, Bass and Scorsese’s old-time editor Thelma Schoonmaker, add shots of De Niro, Pesci and Liotta first riding in their car and then killing the man in the trunk. Scorsese, Bass and Schoonmaker ought to be lauded for this masterpiece of a film opening in which we see the constant use of the colour red: the dying man is stained with red blood, the backlights of the car are stark red and the title of the film itself is red.

This reinforcement of red connotes to a certain negative and sinister quality being attached to these three characters. But more important is the fact how, not just Hollywood but Saul Bass himself seems to have progressed.

This reinforcement of red connotes to a certain negative and sinister quality being attached to these three characters. But more important is the fact how, not just Hollywood but Saul Bass himself seems to have progressed.

Now, for the last look, I’ll discuss an opening from a relatively recent film which has designed its film opening in a very Bass-esque manner. Catch Me If You Can, a biographical crime-drama of sorts, borrows heavily from Saul Bass’ many unreleased sketches and released designs. The brains behind Spielberg’s film’s title credits, Olivier Kuntzel and Florence Deygas, (of Kuntzel+Deygas) seem to have really done their homework.

So, to conclude, we must note how much of an impact Saul Bass has had on film openings and especially title credits. Without him, Hollywood would probably still be following the dull old style of having one dimensional opening credits. Much kudos to Saul Bass!

This still is placed at 2:06 seconds of the video link above.

This still is placed at 2:06 seconds of the video link above.

And so, in this title sequence, Bass firstly has the overwhelming jazz score playing in the background which hints to the importance of jazz in the film. Also, by starting the film by this particular genre of music, Bass seems to connote to how integral jazz is not just to the film but also to Frankie Machine, the protagonist. We also see Bass having a white rectangle transfigure into a hand which, as it happens, seems to compliment the title itself.

And so, in this title sequence, Bass firstly has the overwhelming jazz score playing in the background which hints to the importance of jazz in the film. Also, by starting the film by this particular genre of music, Bass seems to connote to how integral jazz is not just to the film but also to Frankie Machine, the protagonist. We also see Bass having a white rectangle transfigure into a hand which, as it happens, seems to compliment the title itself. This reinforcement of red connotes to a certain negative and sinister quality being attached to these three characters. But more important is the fact how, not just Hollywood but Saul Bass himself seems to have progressed.

This reinforcement of red connotes to a certain negative and sinister quality being attached to these three characters. But more important is the fact how, not just Hollywood but Saul Bass himself seems to have progressed.